Strategy-as-Protocol

Making Strategy Executable, Transparent, and Creative and how Fela Kuti can help

Making Strategy Executable, Transparent, and Creative—and how Fela Kuti can help

I’ve spent the last five years moving from analyzing AI’s impact to actually building with it. In 2020, I led futures work for a pharma company that included synthetic media as a key trend. In 2021, I produced the first report by any media company on AI-generated content—18 months before ChatGPT. By 2025, I was running my own RAG infrastructure, building systems that transform cultural signals into structured intelligence.

That journey revealed something I didn’t expect. The problem wasn’t that organizations lacked insight, or even that they struggled to execute. The problem was that strategy itself was the wrong shape. It couldn’t be delegated. It couldn’t be debugged. It couldn’t evolve.

What strategy is needs to change. That’s why I’m writing this.

Most organizations treat strategy as something between a story and a ritual: an annual offsite, a slide deck, a memo from the top. People are told what the strategy is, but rarely how it actually works as a system of decisions.

The key shift proposed here is simple but radical: treat strategy as a protocol. Strategy stops being a narrative and becomes an explicit, shared stack of frameworks, decision rules, and constraints that both humans and AI systems can operate under. Written in plain, structured text, this protocol becomes simultaneously readable by people and executable by machines.

Here’s what I’ve learned:

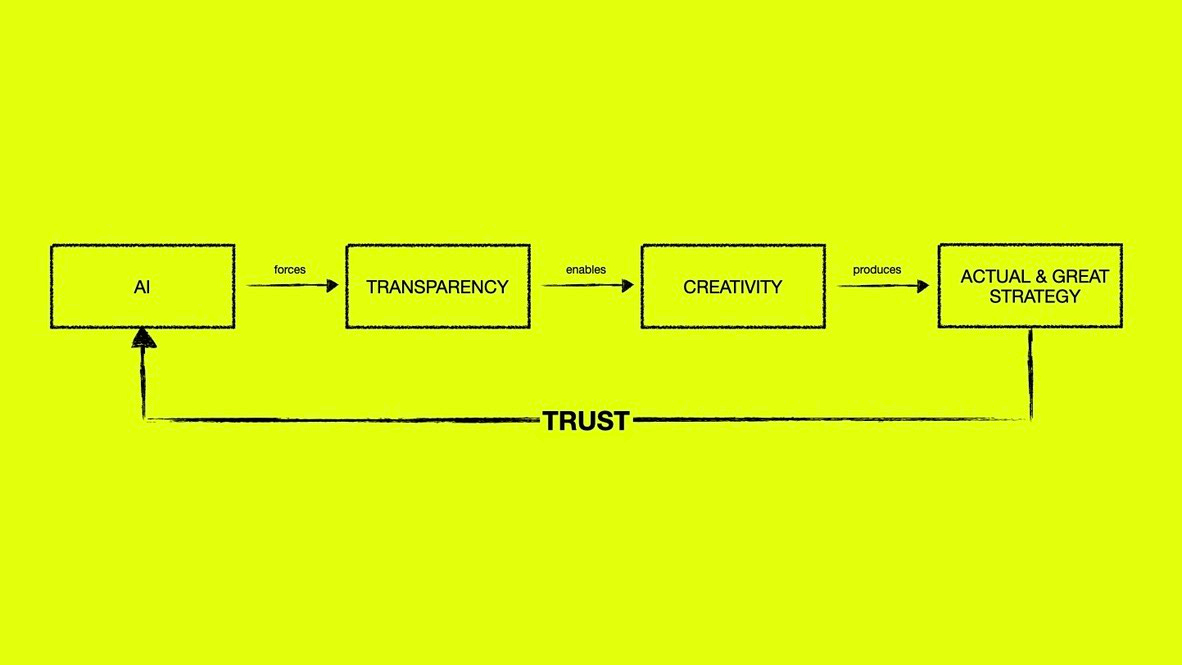

AI forces transparency. You cannot delegate what you cannot articulate. I discovered this the hard way—when I tried to hand off work to a machine, I found I couldn’t explain my own method to myself.

Transparency enables creativity. When the logic is visible, people can engage with it. They can challenge the framework without fear, improvise within boundaries they understand, contribute to something explicit rather than guessing at intent.

Creativity produces better strategy—one that can actually be delegated, debugged, and evolved.

And better strategy? It loops back. It can be handed to AI, which forces the next round of transparency. But closing the loop requires trust; the willingness to let go again, to keep handing off, to stay visible. Trust isn’t a step in the sequence. It’s what sustains the cycle.

A cycle most organizations never enter.

This doesn’t magically fix all the problems organizations have with strategy. But it does make those problems visible and tractable in a way they rarely are today.

Invisible Strategy in Visible Organizations

Even without AI, most organizations struggle not because they lack strategy documents, but because they lack shared, explicit strategy logic.

Chris Argyris’s distinction between “theories espoused” and “theories in use” captures this with uncomfortable clarity. Organizations talk about their values and strategies in one way, but behave differently when things are uncertain or politically sensitive. The gap turns whole topics into “undiscussables,” including how decisions really get made.

“Something that is not discussable, by definition, makes even the undiscussability undiscussable.” —Chris Argyris

In that environment:

Strategy feels like a label attached to decisions after the fact.

Different teams operate under different implicit rules.

People can’t reliably explain why a given decision was made, beyond “that’s what leadership decided.”

If strategy is the starting point—not the output of planning—it has to exist in a form people can actually start from: clear enough to be applied, stable enough to be referenced, explicit enough to be challenged.

AI forces this into the open.

Transparency as Organizational Forcing Function

There’s a common critique of AI: it’s opaque, biased, impersonal. But as Adam Elkus has argued, this critique often misses the target. The algorithm isn’t the decision-maker. It’s a formalization of business logic that humans designed—often the same logic that was already being applied by hand, just faster. “Algorithms are impersonal, biased, emotionless, and opaque,” Elkus writes, “because bureaucracy and power are impersonal, emotionless, and opaque.”

The machine didn’t create the opacity. It inherited it. And demanding “algorithmic transparency” without asking who chose this logic and why just shifts the blame one layer down.

This is also why transparency without trust accomplishes nothing. You can make the logic visible, but if people don’t believe they can challenge it safely, visibility just becomes surveillance.

That’s where strategy-as-protocol flips the script. When you write the decision logic in plain language—visible to everyone who has a stake in it—you can’t hide behind the algorithm anymore. The logic is yours. If it’s biased, you own it. If it fails, you can trace it back.

The protocol doesn’t just make AI transparent. It makes you transparent.

But transparent to whom? And built how?

Zoe Scaman recently diagnosed what’s broken in strategic work: most strategists have no way to encode what they learn. Every engagement is linear, not exponential. She asks: is it AI? Tools? A network, a commons, a protocol?

I’m not a coder. For most of my career, technological systems weren’t a medium I could shape—only observe. That changed. Not through “vibe coding” or the fantasy that AI lets anyone build anything overnight. But something real shifted: the gap between understanding a system and building within it collapsed. Not because coding became easy, but because articulating what I wanted became productive.

I’m currently building a system that transforms raw cultural signals into structured intelligence briefs—analysis that preserves what makes a signal strange while making it navigable to outsiders. Building it forced exactly the reckoning this essay describes.

I discovered that my “method” was partly invisible even to me. When I tried to delegate to an AI, I had to articulate things I’d never said out loud: What frameworks do I actually use? What makes an analysis “good enough”? What trade-offs do I accept without thinking?

The core insight: my work wasn’t about tracking what’s up or down—it was about holding tensions. Culture clusters at both poles simultaneously. The interesting stuff sits in the contradiction, not the resolution.

Making that explicit didn’t constrain my work. It clarified it. Once the protocol existed, execution became consistent, delegable, and improvable. When an output fails, I can trace it back to a specific framework choice and adjust.

This is what I mean by creativity: not freedom from structure, but understanding the system well enough to know where it bends. Which assumptions can be challenged? Which constraints are load-bearing? Creativity isn’t about escaping structure—it’s knowing which walls are structural and which are just paint.

The groove becomes visible.

Strategy as Your Organization’s Groove

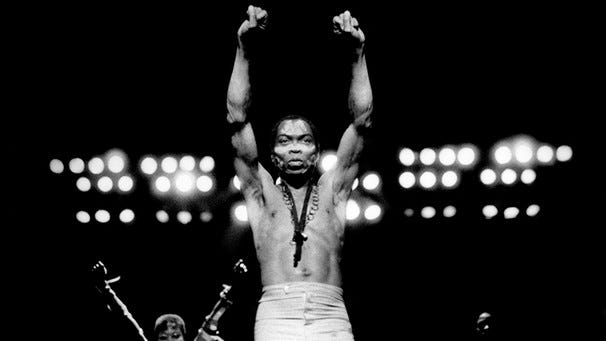

We tend to imagine creativity and structure as opposites. Artists become emblems of freedom from constraint—Escher’s impossible geometries, Borges’s infinite labyrinths, Fela Kuti’s hour-long improvisations. The assumption: real creative work happens when you escape the rules.

The reality is the opposite. Escher was obsessed with mathematical tessellation. Borges wrote within tight formal constraints—short stories, philosophical puzzles, precise logical structures. I have a fractal tattooed on my arm for the same reason: structure isn't the enemy of meaning, it's the condition for it. And Fela's Afrobeat? Built on extraordinarily tight underlying structure.

Fela’s bands operated out of the Kalakuta Republic, a commune in Lagos. Rehearsals were legendary—hours-long, sometimes overnight sessions where the band would cycle through the same groove until it was completely internalized. The 10-15 minute instrumental jams that opened his songs weren’t free-form; they were the band locking into a groove so completely that improvisation could happen within it, not despite it.

Structure doesn’t kill creativity. Structure is the groove.

Structure: Fela’s songs had tempo, bassline, horn riffs, call-and-response. Your protocol has frameworks, decision rules, constraints. The creative work is in designing what to include.

Internalization: The band rehearsed until everyone understood the feel, not just the notes. Your team debates and iterates until the protocol becomes second nature.

Emergence + Evolution: Once locked in, performances became transcendent—solos emerged within the groove, the feel shifted. Your execution works the same: operate within the structure, see what emerges, evolve based on what’s working.

Tight Underlying Structure + Collective Internalization = Emergent Magic

But structure alone isn’t enough. Kalakuta produced extraordinary music, but through coercion and control, not genuine trust. That’s not so different from organizations where people execute within frameworks they can’t see, challenge, or change. The groove without trust isn’t creative freedom. It’s compliance with better acoustics.

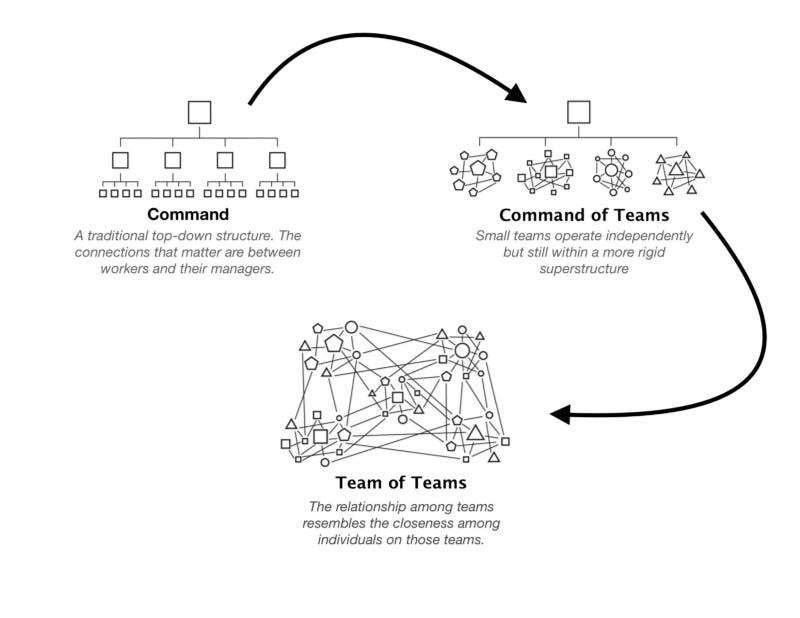

The difference is whether people can change the groove, not just play within it. Gen. Stanley McChrystal called this “shared consciousness”—when everyone understands the operating logic well enough to act without waiting for orders. When your edge teams know the protocol—and trust that they can question it—they don’t need to escalate every decision. They improvise within boundaries they helped shape.

Organizational Learning as a Side Effect

The groove metaphor extends to something crucial: learning.

But learning requires more than visibility. Amy Edmondson’s research on psychological safety revealed that high-performing organizations achieve learning by creating conditions where people feel safe to speak up about failures, uncertainties, and disagreements:

“Psychological safety is ‘literally mission critical in today’s work environment.’ You no longer have the option of leading through fear. In an uncertain, interdependent world, it doesn’t work.” —Amy Edmondson

You can’t safely challenge a black box. You can safely challenge something explicit.

Traditional organizations struggle with learning because most decisions remain partly invisible, even to the people making them. When someone deviates from “the way we do things,” nobody knows if it’s adaptive or rogue—because the way we do things was never written down, or was diluted into a dozen documents nobody reads. Every organization has a slide template. Almost none of them use it.

Chris Argyris called this single-loop learning: you fix problems within existing frameworks, but never question the frameworks themselves. Double-loop learning—where you actually improve the frameworks—requires both visibility and safety:

The frameworks are explicit, so you can debate them.

Deviations are visible, so you can see where reality conflicts with intent.

There’s a shared reference point, so conversations about “should we change this rule?” don’t devolve into politics.

You can only challenge the framework if it is visible—and if you trust that challenging it won’t cost you.

When your strategy is a protocol—transparent, grounded in frameworks everyone helped choose—you’re not being asked to “trust leadership’s judgment.” You’re being asked to engage with something you can actually see. And when you can engage with the protocol itself, you can improve it.

That’s why the cycle loops back. Better strategy can be handed to AI, which forces the next round of transparency, which deepens trust, which enables more creative challenge, which produces better strategy still.

That’s the protocol.

The Real Resistance

None of this happens automatically. You can’t just declare your organization “transparent” and have it materialize.

What you need is: explicit decision rules, psychological safety to question them, audit trails so decisions can be traced, and regular retrospectives asking: is this working? Does it need to evolve?

This is hard cultural and organizational work. It’s harder than buying an AI tool. But it’s also the work that actually makes organizations effective.

Most organizations will stop here.

Not because it’s technically hard. The technology exists. But because opacity is useful (to some). When decisions can’t be traced, no one has to stand behind them. The protocol makes that impossible. The people who designed it have to own it.

That’s the real resistance. Not to AI, not to structure, not to transparency as abstract principle.

To being seen.

Igor Schwarzmann is a strategic consultant specializing in AI strategy and cultural research. He’s spent 15+ years helping organizations like Volkswagen, Novo Nordisk, and WDR navigate the intersection of culture and technology. He gives talks on AI & strategic design at institutions like Domus Academy, and co-hosts the podcast “Follow the Rabbit.”

If you’re building AI capability and want to talk about making strategy explicit, reach out.