Present Archaeology - The Present Problem

Rethinking Knowledge States in Strategic Planning

The Rumsfeld matrix—known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns—has become shorthand for describing uncertainty in strategic contexts. But when mapped against narrative structures, an interesting pattern emerges. Western storytelling consistently follows an three/five arc structure (for the most part): protagonists begin in familiar territory (known knowns), venture into acknowledged uncertainty (known unknowns), encounter the genuinely unexpected (unknown unknowns), and return with transformed understanding.

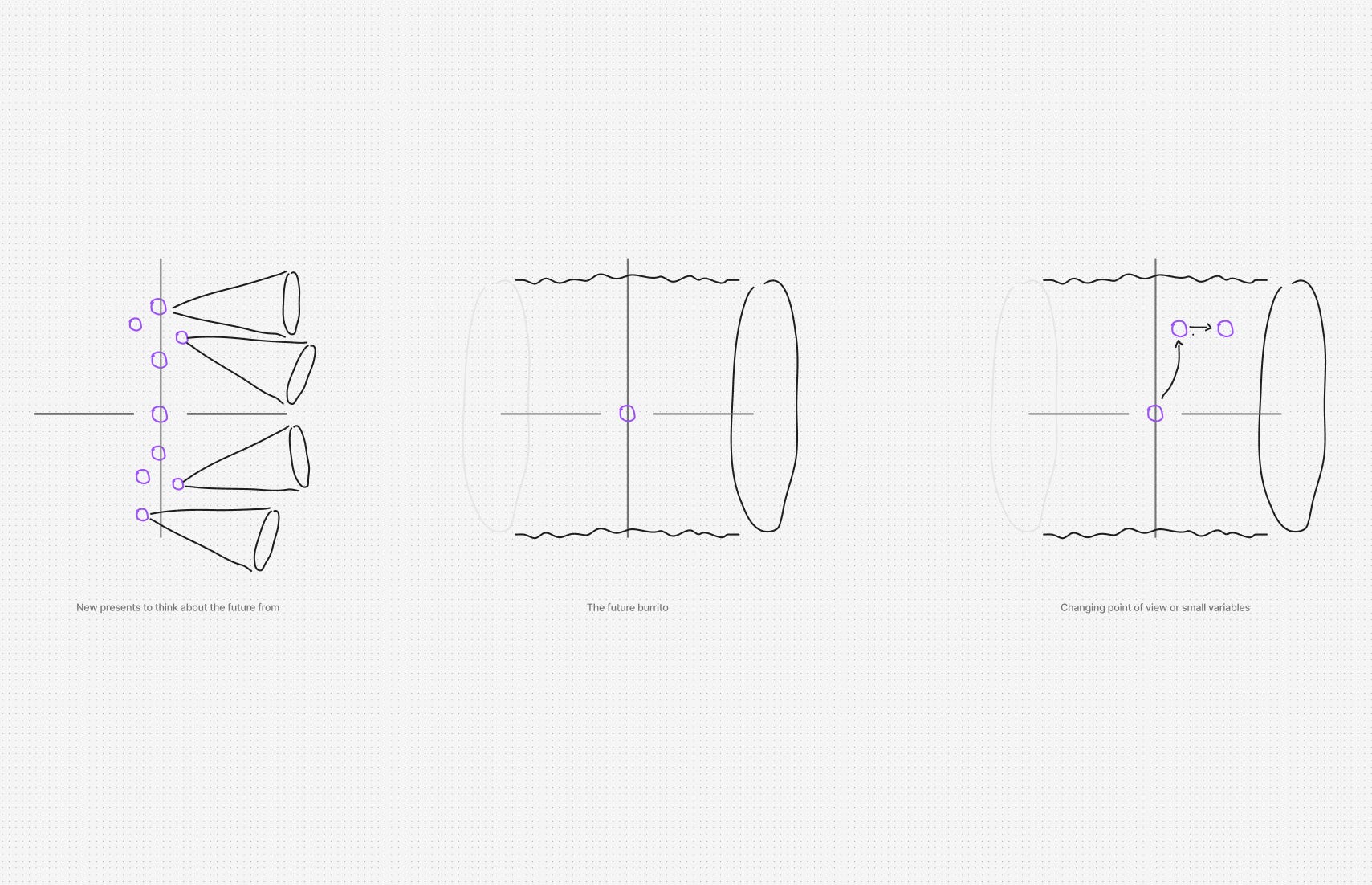

This progression mirrors how we conceptualize time itself. The traditional foresight "future cone" assumes the present as a narrow point of relative certainty, expanding into widening possibilities. We treat the present as knowable and project uncertainty onto the future. Strategic planning follows this logic: analyze current conditions, identify future uncertainties, develop scenarios.

But complex systems suggest a different temporal structure—what designer and co-founder of oio, Simone Rebaudengo calls a "future burrito" rather than a cone. As he observes, "The whole point of the cone is that you're questioning the future...but the starting point is a point. So you're not really questioning your reality." If we acknowledge that "there are many presents at the same time" and the present contains roughly the same spectrum of knowledge states as the future, our fundamental assumptions about strategic planning require examination.

Consider where unknown unknowns actually reside. Rather than existing solely as future surprises, they emerge at the intersection of what we believe we know and what we recognize we don't know. They hide in plain sight—in the gaps between our confident assessments and our acknowledged uncertainties. Organizations routinely miss opportunities sitting precisely at these intersections: where established capabilities meet recognized market gaps, where core competencies interact with strategic uncertainties.

This creates a psychological problem. We assume present comprehension while projecting incomprehension onto the future. But if unknown unknowns permeate the present through these intersection effects, our execution challenges stem not from future uncertainty but from present blindness. As Jan Chipchase observes, "Most of the clues are right in front of us. The key is learning to see the ordinary in a revolutionary new way, to see beyond what people are doing to understand why." We're trying to build futures from foundations we don't actually understand.

The implications extend beyond strategic planning into how we structure knowledge work itself. Traditional approaches separate analysis (understanding the present) from planning (anticipating the future). But if unknown unknowns are systematically generated by the boundaries between current knowledge domains, we need methods for excavating these present blind spots before projecting forward. I like to think of this as Present Archaeology.

"An archaeology of the present looks at things, observing how human activity has transformed – or is transforming – the materiality of the world around people. In doing so, such an approach is no longer directed towards the past in itself... rather, it points towards the future, stressing all kinds of processes of emergence." – Laurent Olivier, The Future of Archaeology in the Age of Presentism, 2019

This Present Archaeology approach shares DNA with strategic frameworks like the OODA loop (Observe-Orient-Decide-Act), but addresses a fundamental limitation. OODA assumes that faster information processing cycles create competitive advantage - the faster you observe and orient, the better your decisions. Present Archaeology recognizes that the act of gaining knowledge itself creates new blind spots. Rather than optimizing for speed of iteration, it optimizes for understanding how knowledge dynamics generate unknown unknowns at intersection points.

Traditional OODA works when external environments are complex but internal knowledge processing remains relatively stable. Present Archaeology becomes essential when knowledge acquisition tools themselves are transforming faster than external conditions. Organizations can no longer assume that more data or faster analysis cycles lead to clearer strategic pictures. Instead, each new capability, each market entry, each strategic initiative creates fresh intersection zones where new categories of unknowing emerge.

This distinction becomes critical in an AI-driven world where our knowledge-processing capabilities are expanding exponentially. AI tools promise to accelerate every aspect of the OODA loop - faster observation through data processing, better orientation through pattern recognition, quicker decisions through automated analysis. But if knowledge acquisition systematically generates new unknowns, then AI acceleration might be intensifying rather than solving our strategic blind spots. Present Archaeology offers a methodology for navigating this recursive complexity rather than simply trying to outrun it.

This suggests that effective strategy requires comfort with present unknowing—not just future uncertainty. Instead of moving from present certainty toward future possibility, we might need to move from acknowledged present complexity toward different future complexity. The temporal relationship between knowledge and action becomes less about reducing uncertainty over time and more about navigating complexity across time.

The narrative implications are equally significant. If unknown unknowns structure both our stories and our strategic thinking, we might be unconsciously applying dramatic frameworks to organizational challenges. The hero's journey becomes a knowledge journey: leaving familiar cognitive territory, encountering genuinely new information, returning with expanded understanding. Strategic transformation follows storytelling logic.

But unlike fictional narratives, organizational contexts don't resolve into clear knowledge states. Unknown unknowns don't get systematically converted into known knowns. They multiply through the very process of gaining knowledge, creating new intersection points between expanding expertise and evolving uncertainties.

This recursive quality—where knowledge acquisition generates new categories of unknowing—suggests that strategic planning might need to account for the unknown unknowns it creates through its own processes. Each strategic initiative, each new capability, each market entry creates fresh intersection zones where new blind spots can emerge.

Rather than treating unknown unknowns as external surprises to be anticipated, we might approach them as emergent properties of our knowledge systems—systematically produced, potentially mappable, and strategically relevant in the present moment.

This is the first essay in a series exploring Present Archaeology across different strategic contexts. I'm curious about applications I haven't considered - do reach out with your thoughts!